Nihil (Part III)

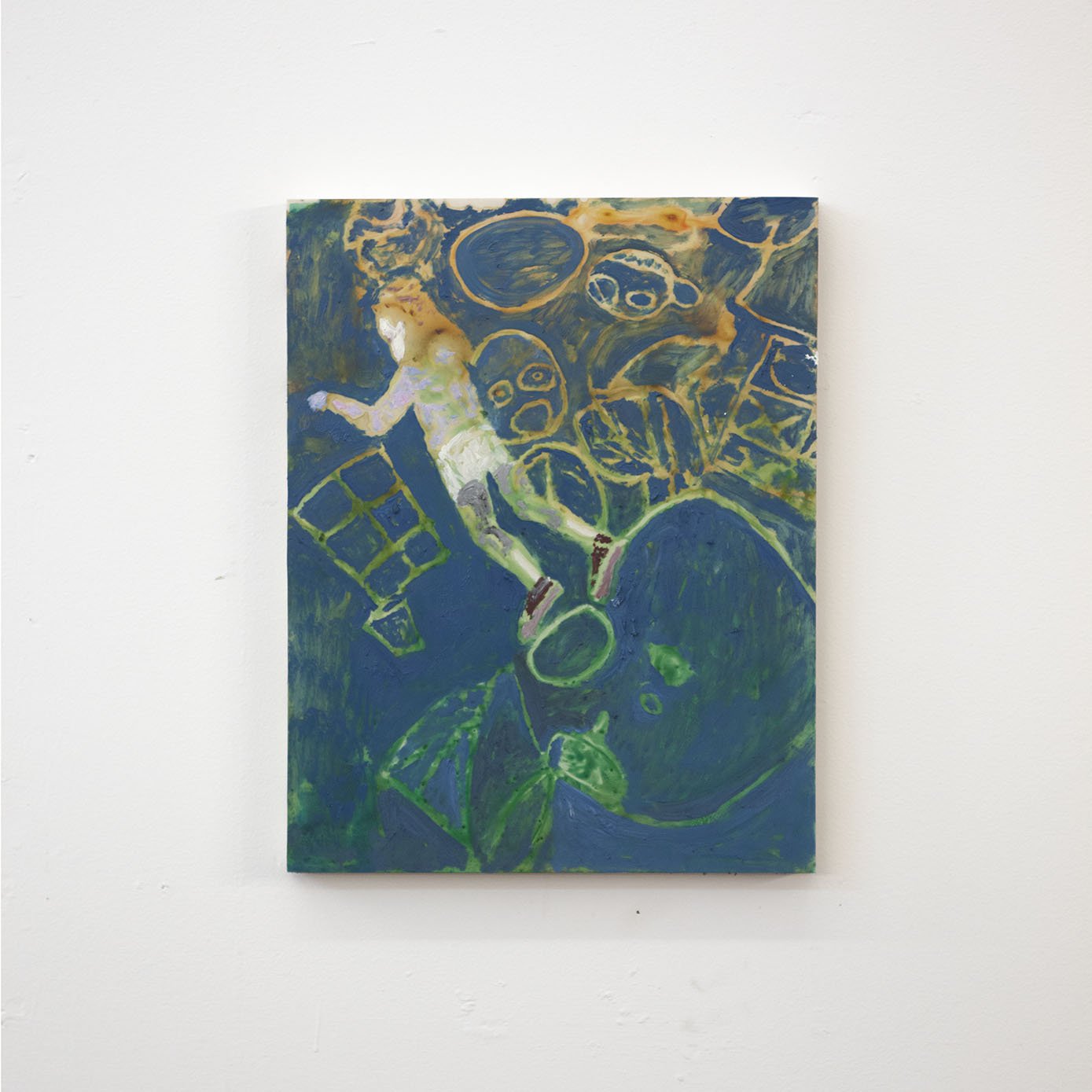

Night Swim (For Eileen) | Mixed Media | 82 x 78 in. | 2021

Installed in Abandon Post Office in Yeso, New Mexico.

Before one says something, perhaps it is better to say nothing. My music has emerged only after I have been silent for quite some time, literally silent. For me, ‘silent’ means the ‘nothing’ from which God created the world. Ideally, a silent pause is something sacred…If someone approaches silence with love, then this might give birth to music. A composer must often wait a long time for his music. This kind of sublime anticipation is exactly the kind of pause I value so greatly.

-Arvo Pärt

I don’t remember exactly when it happened, and I don’t know how, that the word “nihil” flashed in my mind. But it simply did, the five letters, not as a brainy question or concept, but as a “pure, clear word” as poet Stanley Kunitz would put it, unconnected to anything I was doing, reading, or thinking about consciously at the time. Yet day after day, I would see this word in my mind’s eye.

Only recently did I try to uncover something of its meaning and etymology as well as browse through some of the history of the concept of nothing, zero, nil, etc. Much becomes strange quickly. One can get lost in the many latin phrases with their varying implications and applications. Take the phrase vox et praeterea nihil, for example, which translates to “voice without substance.” I wonder how any utterance can lack substance when voice itself is substantive. It implies its own origin. It implies the space it fills, the ears that receive it. “Nothing” it seems, might be little more than the byproduct of language’s limitations. Even Pärt’s “‘nothing’ from which God created the world” seems already to imply the world, as a seed might imply a tree.

The musical structure of Arbos reflects the branching of a tree: a single trunk divides in two branches, which, in turn, divide in two, and so on. The attentive ear of the skilled listener is able to identify various layers in music. All voices start and finish their movement at the same time and the melodic fabric thickens as the descending melodic line gradually extends. This temporally differentiated movement paradoxically creates a sense of majestic immobility. It is as if we would see a single large tree, at the same time noticing its separate branches.

Arvo Pärt’s Arbos Sketch

So it was that I decided to use Pärt’s simple glyph of a tree, from which his musical composition Arbos grew, as the structure or route for my travels throughout New Mexico. For me, the tree as structure is at the heart of the problem of “nothing.” On one hand, it is “nothing” in the sense that my choice to use it is seemingly arbitrary; I could have picked any image for the same purpose and it would have inevitably produced results. On the other hand, the tree will not fail to produce results, which will become the art, which will physically exist in the world.

Each point along the routes of the map is a site of Lethe, that Greek mythological river running through the underworld, the river of forgetting or “oblivion”, which everyone must drink from after death but before before the soul can be reborn. Just as a tree does, a river forks and branches because of natural forces of capillarity. This archetype, as I think of it, has remained a central obsession in my work since 2016, and though Lethe is only more recently informing how I think of the specific spaces I visit, it has, for awhile now, informed the work I make.

“Night Swim (For Eileen)” was made as a kind of simultaneous response to both the musical composition “Fur Alina” by Pärt and a drawing my aunt Eileen made when I was a kid, which hung in her and my uncle’s house from that time until she killed herself.

As a musical composition, “Fur Alina” is minimal as well as implicitly consoling; the silence between the notes and the acoustics of the space in which it’s played have as much to do with what gives it shape as any other compositional device. Like his other tintinnabuli works, it is played with an M-Voice and T-Voice, and while these two voices move in a parallel manner, what makes the piano piece very much alive is the slight dissonance between these voices, the way they move together and yet at a seeming distance.

Trying to understand this for myself by means of a visual equivalent, I liken it not only to the moment of looking at a painting, for example, but to the after-image in the mind’s eye long after looking away. It’s as if the music belongs at once to the past and to an infinite present.

I kept this in mind as I worked on “Night Swim.” For one thing, I hadn’t seen Eileen’s drawing in many years, and though she made many others, it is this one in particular depicting three children drawing with chalk on a blacktop that has remained with me.

I began the work by finding the triad of my aunt’s drawing (after her sister tracked it down for me) in the three children making chalk drawings. I made three distinct studies, one for each child. Then I recreated each study at a larger scale on linen, each one added on top of the previous layer and partially subtracted. The final layer, the fourth, is simply a kind of improvisation to bring some kind of wholeness to the disparate layers through various color decisions and so on.

Working in this way, every painting brings with it something unexpected, and, in this case, it was the sense of a deep submergence in water. Its atmosphere wasn’t something I planned nor could have planned. The figure or figures seem mostly absent. And here again I find Lethe in my work, which seems also to operate like a kind of veil, perhaps between the living and the dead or between this time and another.

While writing this, I found a letter I wrote to Eileen a couple years after her death. It ends this way:

I don’t think you would probably have had much interest in Heidegger but he said the most important question is ‘why is there something rather than nothing?’ But it was Camus who claimed that the most important question is whether one should kill oneself. Almost like the opposite. Like: why is there nothing rather than something?

Night Swim (For Eileen) | Mixed Media | 82 x 78 in. | 2021