Truth, Trauma and Paintings’ Murmurs

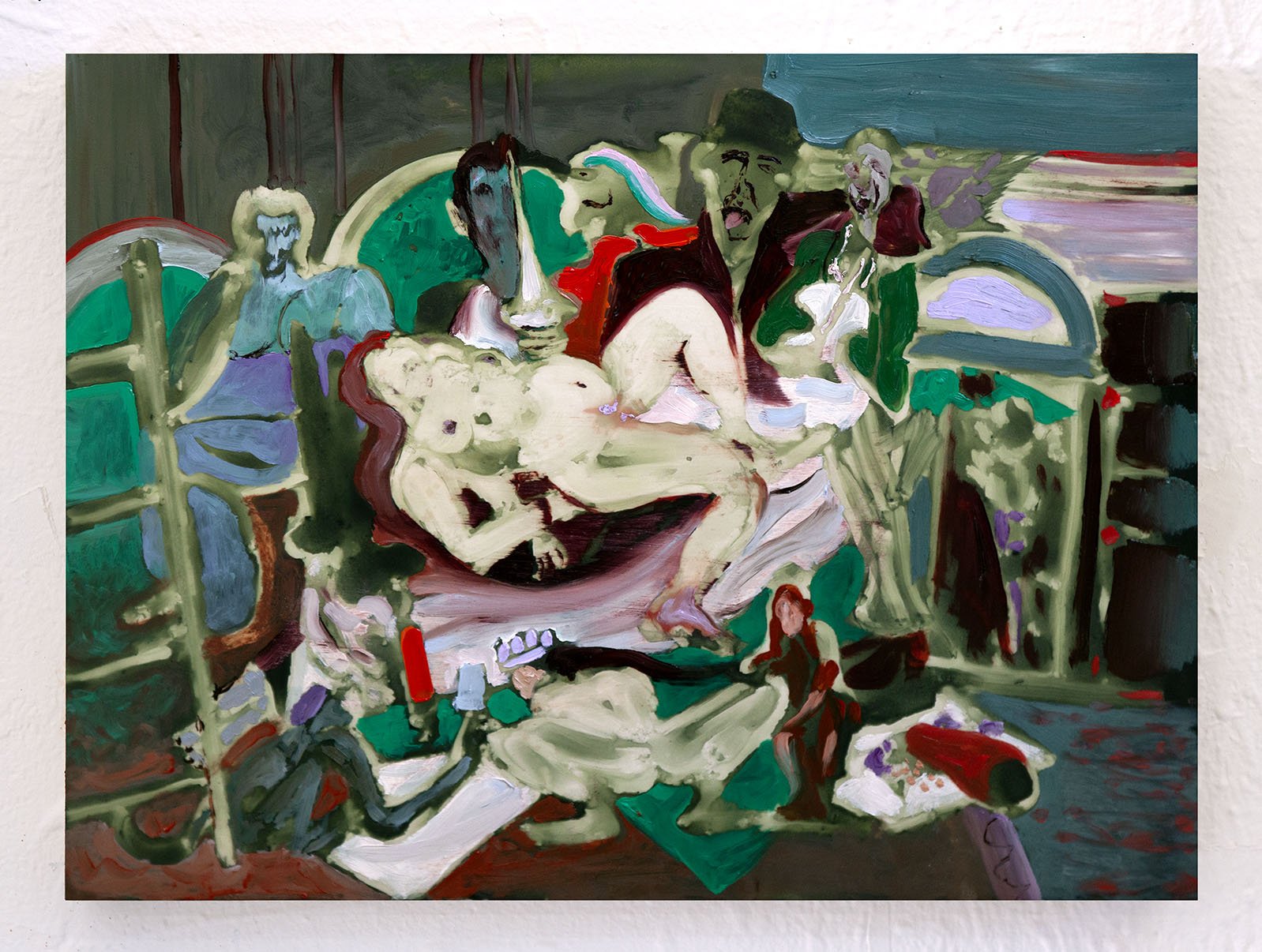

The Call and the Called Out (The Dogs Grow Larger) | Mixed Media on Canvas | 96 x 102 in. | 2019

It’s GMT in London when I speak to Joshua Hagler from his studio and home in Roswell New Mexico where it is ‘mountain time’. ‘Time moves faster at higher altitudes’ Hagler tells me as we connect over WhatsApp to arrange our phone interview. And time and its movement is indeed a fitting image to begin to think and write about Joshua Hagler’s work, for whom the metaphysical movement of time – that is its arcs, ellipses and vestiges – is a recurring preoccupation. And not just time in its abstract sense, but time lived and perceived through the body as imprints of memory and of experience.

But what might this mean in practice, for painting and for making images?

It means painting that grasps at and experiments with the impossible task of giving internal perception a material form on the canvas; it means works that attempt the impossible task of excavating the experience of memory and giving it perceivable contours. It means reconfiguring the psychological shape of trauma, and attempting to recover what is repressed or obsolete.

But that’s not to say that Hagler’s work is overly abstract: an eclectic selection of visual referents range from German Expressionist painting to cult 70s horror films; indie science fiction to music videos by Madonna and Michael Jackson, and New England morality tales about the devil.

In a suite of works inspired by Max Beckmann (1884-1950), Hagler looks back to the German artist’s theatrically staged scenes of cold-blooded torture to examine the human propensity for violence. Beckmann’s The Night (1918-1919) is a now canonical image of the German Expressionist movement which emerged out of the First World War. Inspired by the artist’s eye-witness sketches in the operating rooms and morgue as a medical orderly in the German army the painting depicts a macabre staged scene of arbitrary and surreal acts of violence that expresses Beckmann’s disillusionment (like many other artists of the period) with humanity’s compulsion to create its own versions of hell. The work (along with other highlights of art history such as Jan Brueghel’s Hunters in the Snow from 1565) has been a recurring touchpoint for Hagler, who, like Max Beckmann, also experienced a turning point in his artistic interests stemming from disillusionment - in this case Hagler’s position as witness to the rise of Trump and right wing nationalism and violence in his native USA from 2016.

However Hagler’s work importantly eschews any glib analysis or over dependence on art historical referents, which he finds more typical of apologies and excuses on the part of the artist. Any attempt at interpretation by way of grandiose symbolism is counter-productive for the viewer of these often operatic paintings that twist and turn, stretching away from thematic concerns that are too easily read. Hagler is an artist who is always thinking about how images work both physically and psychically: how they slip away, become overlaid, obscured, or repressed. This is painting and occasionally sculpture in which process - that is the phenomenology of making and experiencing images both as artist and perceiving subject is, if anything, the unifying thread among the artist’s corpus of work. The often evocative and elaborate titles work as invitations to a narrative, but these are narratives that are at best half glimpsed in works that do not pronounce their message or intent, but instead ‘murmur’- to use the artist’s own term - from somewhere within.

After Max Beckman Studies | Ink, Oil on Polyester Film | 12 x 16 in. | 2019

A large scale work (260 x 240cm) such as The Call and the Called Out (The Dogs Grow Larger) after Max Beckmann, 1919, 1947, 1950, 2019, shows Hagler’s habitual strategy of overlaying scaled up images from different separate studies on top of one another, in this case a sequence of studies taken from three different images by Beckmann. At each stage of the layering, large areas are peeled or scraped back to reveal unexpected juxtapositions and distortions with the image plane beneath. The result is a painted surface that is both chaotic and semi-figurative, an overlay of different moments and scenes that coagulate into something familiar yet strange.

In works such as A Horse is a Boat a Man is a Chair and the Ocean is a Room into which Every River Empties, (2016) surreal shapes like multi-coloured viscera slither across the canvas and with them any fixed interpretation of what it is we are looking at also slithers tantalisingly out of reach. A horse’s head smears into an abstract tessellation; a hand holds a red telephone receiver. What we are left with is painting as a surface that reveals itself to have simultaneous worlds both above and beneath, a technique of making images that allows the multiplicities of time, process and memory to be visualised, or the imagined possibility of other worlds and narratives that are synchronous with our own moment. These are paintings that are consonant with the images of memory as seen in the mind’s eye, imprints of past images in which some parts fade, some become more vivid, others shape-shift entirely or reveal themselves to be stranger than first perceived.

The technique - which Hagler has been experimenting with since 2016 - invites a descriptive vocabulary perhaps more familiar to archaeology, as the viewer’s eye is tempted into a process of ‘excavating’ or ‘unearthing’ the layers of paint and image that are buried. Or we might even be inclined to borrow from the language of psychology to see these sediments of images as a quest to access past repressed psychic experience. This practice invites slow looking over the expansive terrain of the image, in contrast perhaps to the over processed visuality of contemporary visual culture with its torrent of daily images projected from ubiquitous and multiple screens. Perhaps we’ve become so used to accessing surplus knowledge in our information saturated age that painting that offers only an uncertain emotional response feels somehow evasive. This is also a political choice for Hagler – a way of interrupting the over-simplified and polarising discourses characteristic of our prevailing climate of populism, in which nuance and reflection seem to be regularly jettisoned in favour of the loudest and most violent voices and their conviction of bearing ultimate and incontrovertible truths.

Make It Rain | Mixed Media On Canvas | 120 x 96 in. | 2019

In The Society of the Spectacle, French philosopher and founding member of the Situationist International group Guy Debord wrote in 1967 :

‘... just as early industrial capitalism moved the focus of existence from being to having, post-industrial culture has moved that focus from having to appearing… all of life presents itself as an immense accumulation of spectacles. Everything that was directly lived has moved away into a representation. ’

Music Video I | Ink, Oil On Polyester Film | 10 x 8 in. | 2019

These are prescient words, written from a past in which 24hr rolling news images and the ‘scrollification’ of all personal experience, consumption and production to fit the interface of social media had not yet colonised most forms of human perception and praxis. Hagler is similarly interested in the seemingly insatiable appetite for spectacle in our channels of mass media, in particular how contemporary atrocities tend to get reabsorbed and expressed through our media and popular culture, which often exploit human trauma as both the raw fodder for entertainment and in the service of political theatre - a phenomenon that has led us to an estrangement from reality (as Debord himself philosophies).

In a body of work called Falling Through the Dancefloor created in 2019, Hagler responds to the twenty-first century epidemic of mass shootings in America. The Music Video series (I- IV) takes its point of departure from Madonna’s music video ‘God Control’ which references and re-enacts the infamous 2016 Pulse Club shooting in Orlando in which Omar Mareen shot dead 49 people. Hagler takes a series of scaled up studies of stills from the video and overlays them in his habitual technique, scraping away layers as he progresses, in a process of looking backwards and beneath as well as forwards and above, and in doing so echoes the temporal sequencing of the music video’s narrative which flashes forwards and back, to the ecstatic dancing before the massacre to the funeral of the victims.

My God | Mixed Media On Canvas | 120 x 96 in. | 2019

Trace of the M(o)ther IV | Mixed Media On Canvas | 60 x 48 in. | 2019

The video is intended as an intervention into gun-crime in the US (a ‘wake-up’ call as one of the song’s refrains deems it), but in practice the video arguably fetishizes the glamorously dressed patrons in their sequins and spangles who writhe first in the ecstatic pulsing rhythms of dance, and then in death throes. In such Hagler plays with the ambiguity of physical ecstasy versus agony, not unlike rousing Christian baroque images of martyred saints. Madonna, wounded at the climax of the choreographed blood bath assumes the status of a martyr, who like other ‘icons’ of contemporary culture has become a secular replacement for quasi-spiritual worship by fans and followers (a theme Hagler reprises in My God, 2019, a work inspired by Michael Jackson). This alignment with the language and praxis of religious works about martyrdom is reflected in the numbering and dimensions of the Music Video sequence, which echoes the images associated with Christ’s passion known in Catholic visual culture as the Stations of the Cross, and which serve as a meditative focus for prayer. (For Hagler, as for many who experienced a rigorously devout childhood, religious images imbibed in early years cannot but continue to haunt his consciousness).

Hagler returns to the subject of gun crime in Trace of the M(o)ther IV a composite image made from portraits of a mother killed while shielding her child, superimposed with images taken on the day the baby was born. The combination creates a third image in which the representation becomes blurred and semi-recognisable. The image seems to question whether painful narratives still exist even if we disfigure them or attempt to disguise them: are they still there, is the pain redeemed or mitigated in some way?

Mother and Child 2015-2019

Hagler experiments with this strategy and theme again in Mother and Child 2015-2019; a cut up sequence of nine paintings inspired by stills from Lars von Trier’s indie sci-fi film Melancholia (2011). The source images are taken from a scene in which one of the film’s protagonists (Claire) becomes aware that she and son are about to die from an impending collision with the rogue planet Melancholia that is headed towards Earth. Hagler cut the original work into smaller panels, which he then deposited with the dregs of paint from his palette while working on other larger paintings. In doing so the initial image became disfigured, rendering it almost unrecognisable, but with the indelible vestiges of the primary image (and the pathos of the narrative moment it draws on) still murmuring from the baseline of the canvas.

This process of disfigurement by distortion or deposits of discarded paint speaks more widely to Hagler’s recurrent preoccupation of what painting can do to process violence and trauma - both the inescapable spectacle of it as well as the epigenetic trauma carried in bodies and psyches. As a thematic it is in a sense something that is both internal and external to the artist himself: in his position as a witness and commentator on contemporary violence, as well as in his personal history: the artist lost his own brother in childhood and refers often to the lasting effects of this family trauma and the weight of his parent’s projected grief. As Hagler suggests he was ‘carried by [trauma], just as one was, at one time carried in the womb’.

What potential we might ask then does painting have for dealing with trauma, especially being a sensation and psychic state that breaches the limits of representation, extending beyond the existing terms, words, images that make sense of it as an experience? Culturally it seems we continue to lack a sufficient language to adequately process it. Writing on art and trauma, art historian Griselda Pollock has suggested that there are five defining features of trauma; ‘perpetual presentness, permanent absence, irrepresentability, belatedness and transmissibility’. Thinking about Hagler’s multi-dimensional canvases with their elliptical representational coherency, many of these features are broached in his insistent repetition of motifs (such as the red telephone), and his interest in visualising the distortions of memory and the vestiges of psychological experiences.

Hagler’s habitual layering technique also seems fitting when we dig deeper into the etymology of trauma itself, which comes from the Greek word for ‘wound’. Trauma is, in other words, an opening, a piercing, an entry into the interior of both body and psyche, and in such is a metaphor that aligns with the artist’s painterly processes with its incisions and erasures that reveal uncertain and unfathomable interiors. But if painting for Hagler is an experiment in visualising and giving form to trauma, it is also something that offers the potential for resurrection or even reincarnation (an aspect of his practice that invites a loose comparison with the nineteenth-century Theosophical spiritual movement derived from the writings of Helena Blavatsky.) Hagler talks poignantly about the synchronicity of loss and arrival, of losing one soul and welcoming another, when thinking about the birth of his daughter in light of the loss of his brother. He talks about the image space as a place of ‘safe passage’, of willing the not yet arrived into presence. This idea is echoed in his sonogram series of paintings, inspired by the darkness of the sonogram screen that becomes a canvas on which a picture of presence is conjured up through vibrations - of someone not yet become, not yet here.

Hagler’s entry into parenthood has impacted his work in profoundly creative ways. The hallucinatory 24- hour days of life with a new-born provided a productive shift in consciousness for the artist and a receptiveness to new ways of thinking inspired in part by the agitated sensory awakening of sleep deprivation. Unusually for a male artist, Hagler takes us beyond the well-worn art historical trope of the mother and child or ‘Madonna and Child’ from Christian imagery, one that has stilled the complexities of the maternal and filial relationship into an over familiar and hence empty archetype. Through Hagler’s many depictions of mothers and children, from those imbued with tragedy in the case of mothers and children killed in New Mexico shootings to the images of his wife breastfeeding their baby daughter in the dark, the recurrent mother figure that haunts Hagler’s work seems to speak to the universal psychodrama of the maternal and filial bond - one that is buried and obscured in our patriarchal culture in which the symbolic dialogue between father and son (from the traditional language of psychoanalysis and the Oedipal myth, to our creation stories) is the ur-narrative. Although obscured, stained and overwritten, Hagler’s paintings seem to suggest that the long psychic shadow of the mother can never be eradicated.

Holy Mother | Mixed Media on Canvas | 102 x 96 in. | 2020

Holy Mother (Study) | Ink, Oil On Polyester Film | 10 x 8 in. | 2020

In Holy Mother, Hagler offers a moment of levity into this discourse – overlapping studies of his wife, posed on the bed, Venus-like while pregnant combine with the double-entendre of the painting’s title, which could either reference the over-familiar traditional Christian mother of Jesus, or work as a casual exclamation appreciating a sexually attractive woman (‘holy mama!’). This juxtaposition, while comical, also points to the way in which visual maternal role models in our culture flatten out female sexuality in limiting ways.

Perhaps then we can see Joshua Hagler as a painter who is not a creator of new worlds but a revealer of the ones already there, murmuring beneath the surface of what we take for granted, of what our culture makes (allows?) to be most visible. Often he has used found objects such as discarded railway signs and scrap wood gleaned from the desolate ghost towns that he toured on the Lewis & Clark trail of the US; fragments of already finished stories that retain vestiges of presence in incoherent and poetic ways.

Some of Hagler’s latest works draw on the theme of truth and memory in compelling ways. ‘Aletheia’ is the ancient Greek concept of a type of disclosure of truth, what the artist has described as a ‘gate opening to return one’s memory’ (it is the opposite of oblivion, bestowed in the water of the Greek river Lethe). For Hagler the concept of Aletheia suggests that through the restoration of our memories, whether primal, primordial, epigenetic or otherwise, one can retrieve the truth. Or, more to the point (as Hagler says) offer a ‘realignment with our purpose’. It is, also, one of the names given to his daughter; ‘Mila Aletheia’, to whom he has written the poem ‘Take Care’.

This sense of recuperation through the image, through looking and through memory can also be apprehended elsewhere in his work, particularly those of the desert landscapes of New Mexico which form the basis for the ‘Drawing in the Dark’ series and symbolise for Hagler what he calls a ‘repatriation with nature’. These large- scale chromatic paintings overflow with magma-like and geological forms, conveying the spiritualism of the American landscape that has enchanted artists such as Georgia O’Keeffe and Agnes Martin and also echoes Paul Cezanne’s legacy of obsessive looking and exercises in visual perception with the landscape of southern France.

Hagler’s paintings – of landscape, of loss, of trauma, of presence are an invitation to look more deeply, even if that is through a glass darkly.

Aletheia | Polymergravure Etching on Somerset Soft White Paper 300gsm | 54.5 x 78 cm. | 2021