Drawing in the Dark

Drawing in the Dark

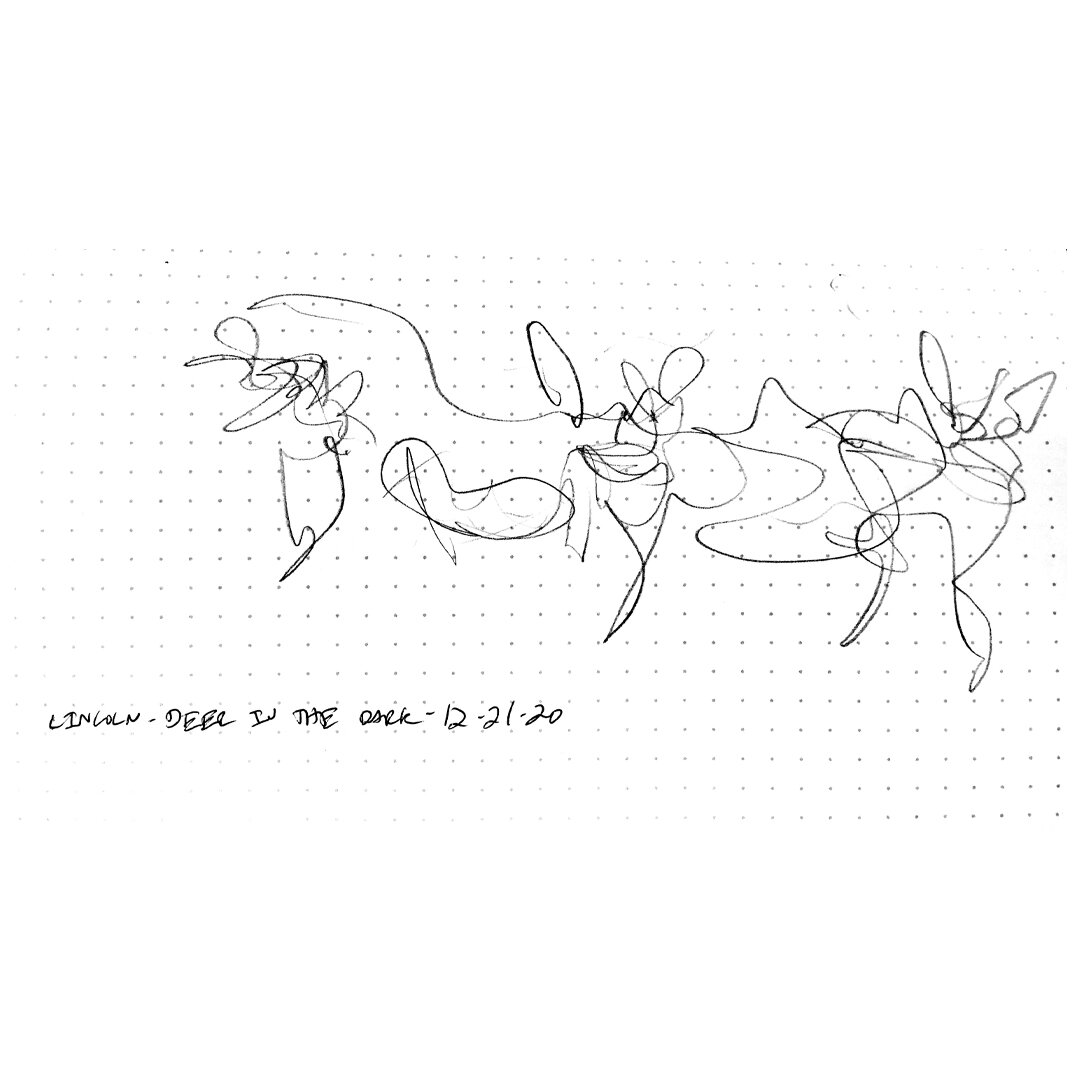

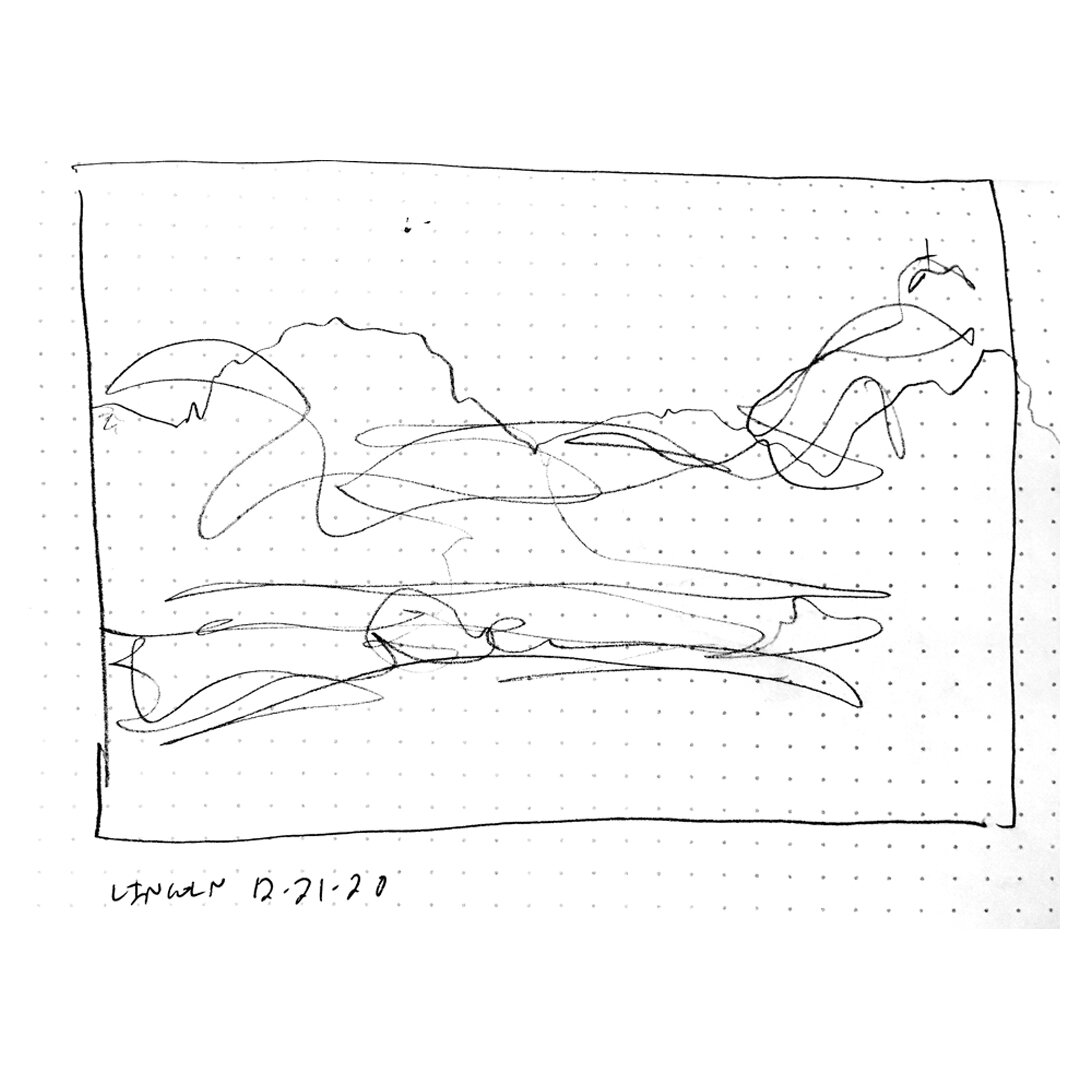

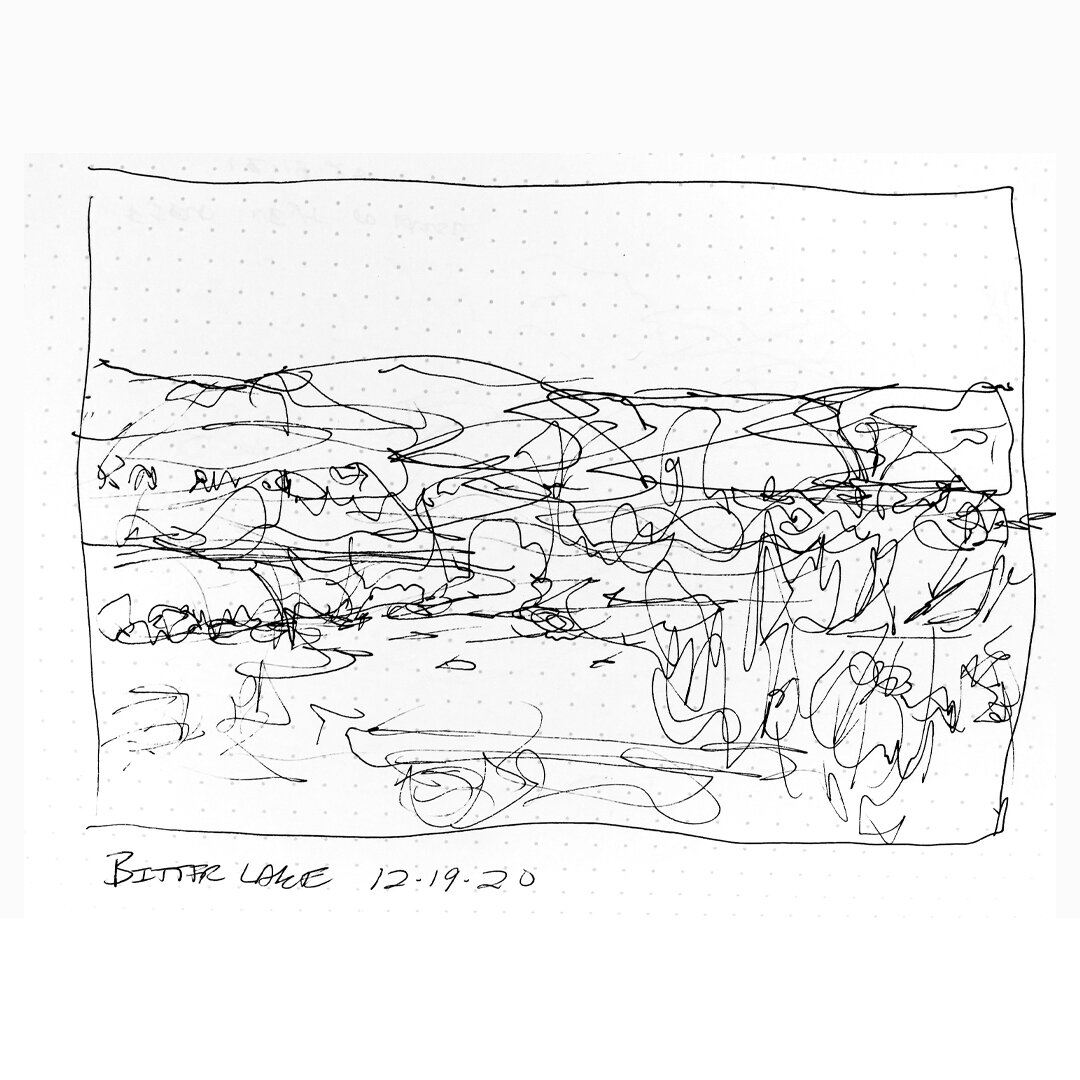

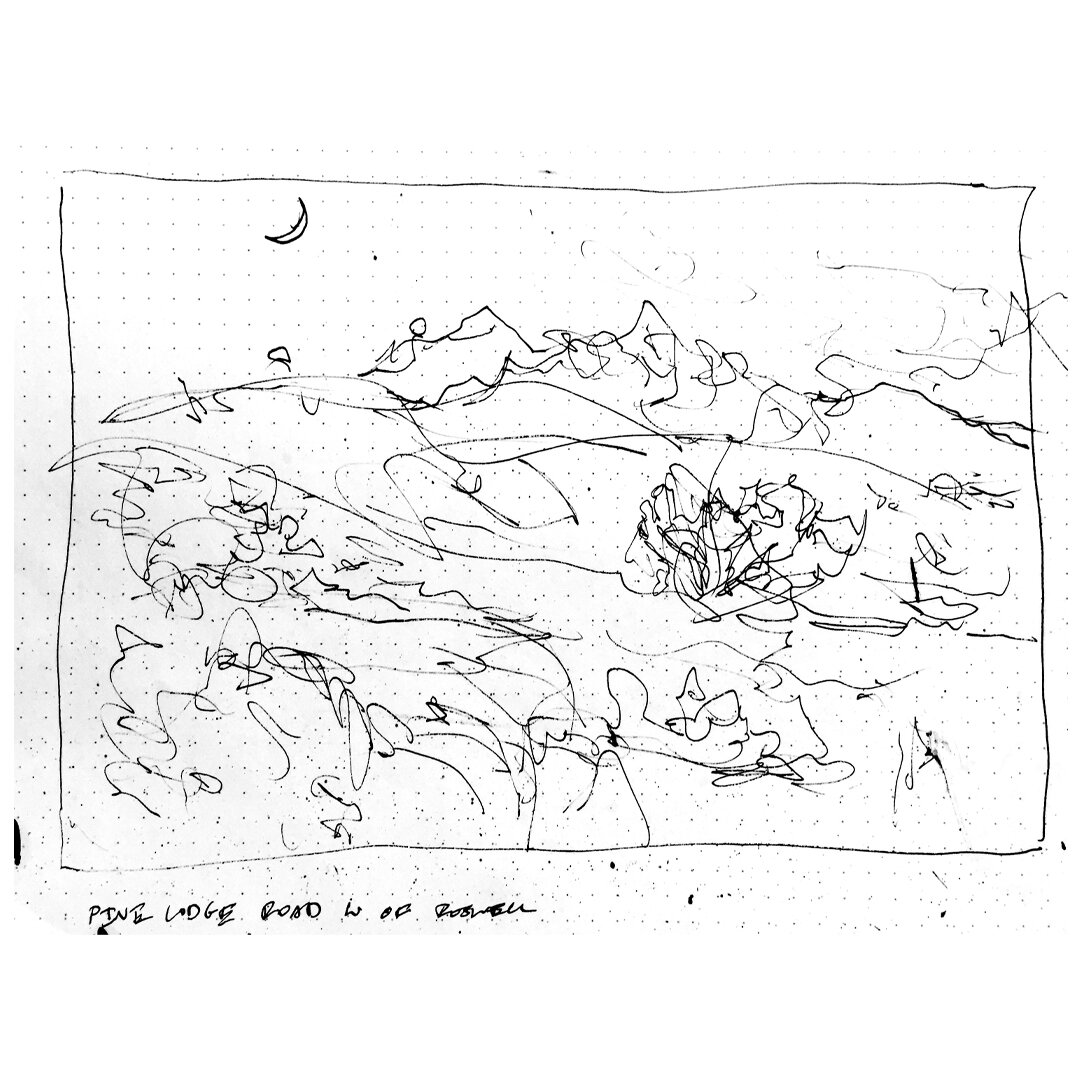

In the evenings leading up to the 2020 solstice, I made blind contour drawings of the landscape in New Mexico’s Hondo Valley and Lincoln National Forest as Saturn and Jupiter inched toward their eventual conjunction. I used only available light to view my sketch pad: the remaining light at dusk, the crescent moon, street lights, Christmas lights from faraway houses, and passing cars along the freeway. On the night of the Solstice and Conjunction, I decided to draw in Lincoln, an old Spanish-speaking settlement in the Bonito Valley, now an unincorporated village with a couple tourist stops, where Billy the Kid was once jailed. I walked out onto a field behind the old mission church there toward the wilderness. It was already quite dark and my eyes were focused on the sky. For reasons I’m not able to explain, there are, for me, always any number of uncanny symmetries in and around Lincoln. I carry a few strange stories with me about my experiences wandering around there at night; this was not the first time. As I walked behind the church there were two nearly symmetrical mountain peaks on the left and right, one north of the other. Above the southern peak was the pair of stars, Jupiter and Saturn in their closest proximity (they never did appear to converge), while above the northern peak a brightly lit cross stood in observance of Christmas. I sensed a presence nearby which I took to be the symmetry of the scene itself and drew with my pen very quickly, as well as I could given the low visibility of my surroundings. No matter how late at night, the sky is always brighter than the landscape, so long as there is little light pollution from cities. The trees and mountains become black, and it’s difficult to discern one thing from another. For awhile I stood and drew there, page after page, in my sketchbook, trying to see into the darkness as well as possible. After awhile my eyes were able to adjust better to it. Only after several drawings did I finally understood that the presence was animal. That’s the way it is in the dark; the mind registers presence, then animal, then, only later, if at all, which. Not more than twenty feet from where I stood were two still and silent deer, staring directly at me, perhaps hoping I might pass without noticing. Excitedly, I tried to draw them as quickly as I could, though mostly blindly. In focusing on them, and just beyond, I became aware that there was not just two but an entire heard. There might have been another dozen standing some distance behind. No doubt they had been here watching me all this time.

Drawing is no more similar to taking a photograph than it is to making a painting. To draw what is around oneself from where one stands is an expression of being in the world in the most direct and yet most mysterious way I know. Of course there are innumerable ways to draw, but to do so without correction or concern about proportion and accuracy is to lose oneself to the ground, and on that ground, to be assisted in some ineffable exchange between the hand on the flat plane and the eye on the distance. It is easier to draw in this way when visibility is low; as light diminishes, alertness sharpens. A drawing made in a heightened state of alertness in relation to what is hard to see is not a description so much as an accrual. The busy hand acts as pressure valve for the buildup of particles acting on cells acting on instinct. The hand rushes to keep up with the energetic charge. It is as sharp an intention toward the world as there could be, and as profound an exchange: the expansion of interior space for the intensification of the external. In drawing in the dark, it is less possible to report on what is seen than it is to describe what is felt in the gap between one’s own position and what is all around. For me, night drawing carries the possibility of repatriation to the real, the simple acknowledgment that to describe is necessarily to create. After all, what makes the world most real to the senses but what is also most numinous in our contact with it?

The Picture a Sound Makes

About nine months before I began tracing the progress of Saturn and Jupiter’s conjunction through my night drawings, I began drawing the progress of the fetus as it developed in my wife’s womb ahead of the birth of our daughter. I did this by drawing from the sonograms we periodically brought home. Much else was going on in our lives and in the world as the fetus developed. Looming large in my mind was the Covid pandemic she would be born into. I was anxious about how vulnerable my wife might be in the late stages of pregnancy, and eventually, my daughter as an infant. It was impossible not to think of my infant brother who died when we were kids and of that trauma and its many implications for my family, all the more alive for its silence.

A fetus, especially at the earliest stages, seems something other than human. The idea that information retrieved by sound waves can be translated into imagery is one that never ceases thrilling me. Both technology and fetus seem paradoxically ancient and futuristic. The fetus is a prehistoric totem, a cave painting, an astronaut, like the one in 2001: A Space Odyssey, drifting into the darkness of space.

Unlike the night drawings, the sonogram drawings were made through indirect observation. In daylight, it is easy to observe what’s in the sonogram and, more or less, to copy it. I was happy to draw them in this way in order to make a record of the development of the fetus, but I wanted something else if I was going to use any of this visual information to make paintings, as I had planned. In the way that sound waves carry information that can be reliably translated into this strange image called a sonogram, perhaps I could use the technology I had available in my studio to translate my drawings into another kind of imagery, not of the fetus, but of the development itself, to compress this development in time by superimposing all stages at once. Using simple Photoshop layers to do just that, I began to think of the layering, the digital superpositioning of my drawings, as the real drawing, and my original sketches as smaller components. It was a way to visualize what can’t be copied. Metaphorically speaking, the digital process was akin to translating the image back into sound waves, echos carried in time, redundant except by their diminishment in volume and clarity as they promulgate into the future.

And that’s what the superpositioning of similar images does; it diminishes the clarity of each image through the redoubling of it. The idea of flattening the stages of development onto a single two-dimensional image and thus making them all nearly illegible held a certain significance to me. The implication has to do with memory, itself a kind of echo decaying in time, the reality of which inevitably changes beyond recognition. It is in this kind of darkness that we fashion our narratives and construct a self.

The loss of legibility to the image through the digital layering process, incidentally, has something in common with a mode of painting typical of my practice. Often in my paintings I employ a method of layering paint by which I subtract as I add. There is a material plasticity to each new layer added, which makes it easy to remove from areas of the substrate, but only imprecisely. I enjoy this way of working because it occurs to me I’m working backward, in a sense, as I work forward in time. Applying this kind of digital layering of sketches to make an original digital drawing and then physically layering the painted approximations of these digital drawings, is a way to compound the layers beyond what I usually could, if working only digitally or only physically. In this sense, the paintings are an accumulation of these many parts: sound waves translated to image, the hand tracing the image through drawing, the digital superpositioning of the drawings, the digital images translated to paint, the paint partly eviscerated, and, finally, the total residue of that process. There is so much change occurring at each stage of the process that the result is unpredictable.

It came as a real surprise to me that the paintings, at the tail end of so much technology, would appear, in some cases, totemic, or even ancestral, and, in others, totally unrecognizable as having ever dealt with the fetus as an originating focal point. Of the latter, I would say they appear simply as space, or rather, place. The compression through superimposed stages of the fetal development becomes landscape. If I try to name the place it becomes, it is a kind of Elysian Passage for transition, for those departing to commune with those arriving, for one to mingle with another. It is a place both internal and external. It is neither sentimental nor sympathetic; it simply hums from its own uncertain distance. I’ve come to think of the overall process as a kind of accidental cosmogony which happens where my own curiosity intensifies and the usual neurotic appeal to rationality falls away.

My daughter was born after I finished the sonogram paintings, three days after the anniversary of my brother’s death. She was delivered by emergency c-section. The nature of the emergency would normally have prevented the baby coming to full term in the first place. We were lucky. The near-crisis felt like a response to a deep instinctual drive at work in making the paintings, one I would have been too self-conscious to speak at the time, that to desire opening a space where one encounters the other, was to wish for my late brother to assist in her safe arrival. The childish truth of my admission—I see it typed on this laptop, sitting out on our back porch as the sun already begins to set at 4pm—takes my breath away. I like believing, though of course I can prove nothing, that the very same drive was at work in the minds of the first artists. The evidence of where they came from, what they were a part of, was all around, and I can only imagine it informed their ideas about where they might be going.

Between Earth and Here

In one sense, to trace the progress of Saturn and Jupiter each night was to create an excuse to drive out into the countryside to draw and to have parameters for how many drawings I should make or how many layers the eventual resulting painting might have. I knew from the outset I would draw in Lincoln on the day of the solstice, the final day. But I was also genuinely drawn to two stars closing the gap each night. I liked the paradox of how near they seemed to each other from where I stood and how far away they actually were in space, almost half a billion miles apart. I grow more and more skeptical of metaphor and meaning, in general, to describe reality, yet I can’t help making meaning. If nothing else, seeing the stars in metaphorical terms tells me what I care about: nearness, union, bridging of gaps. The more isolated, and even exiled, I feel from the world I lived in before moving to New Mexico, before Covid, and before child, the more repatriated I feel to something ineffably familiar and deeply true about the earth being my home. In this way, my life mirrors the paradox of the two stars: I feel close to earth even as I feel estranged from the culture at large, and, I suspect, probably because of it. When I am thinking of the distance between two planets, I am thinking of other distances. Some distances are measured in time: the distance between earth before and earth now. I am thinking about the distance between my infant brother and infant daughter in both time and space. The distance between my perception of reality and what it might really be, if the framework of such a question even holds up beyond what I have language for.

“Between Earth and Here” is the first painting I’ve ever made with only quick sketches drawn at night for reference. As with the sonogram paintings, I superimposed stages in an overall process onto a flat surface. That is, I layered the nighttime sketches, compressing several nights onto one canvas. Most landscapes I’ve made over time have only been called such because that’s what they seemed to be: a painting of a place. If the place is “merely” an interiorized space, that’s fine with me. I believe in interior landscapes, or, put another way, I disbelieve interior/exterior dichotomies as a reliable description of reality.

Several surprises occurred in making the painting. First, the symmetry of the peaks in Lincoln are improbably accurate to the peaks as I actually encountered them. The process of making a painting by subtracting layers as they’re added typically means that scale relationships cannot really be maintained as originally encountered or drawn. I was also surprised by what happened to the animals as they were partially added and subtracted from the picture. In one sense, there is an accuracy to them because of how camouflaged they are in the landscape, just as they were when I encountered them, even if only because of the mark making and not because of the light. I like, too, that even after it’s discerned that there are animals in the landscape, it’s not obvious which kind. That’s accurate to the experience of encountering an animal at night. It’s the accuracy of the painting that surprises me more than anything. But beyond what’s accurate about it, is also what’s different, that the animals did not materialize into deer as they did when I was in Lincoln, but look alternately like wolves, jackals, or even something amphibious. This is where the painting takes on an identity of its own, where it separates itself from my intention, and asserts its otherness. Like the paradox of the two stars being both close and distant, so too, for me, is the painting.