Nihil: Archaic Brother

Archaic Brother | Installed in Abandoned Bible School at Fort Sumner, New Mexico

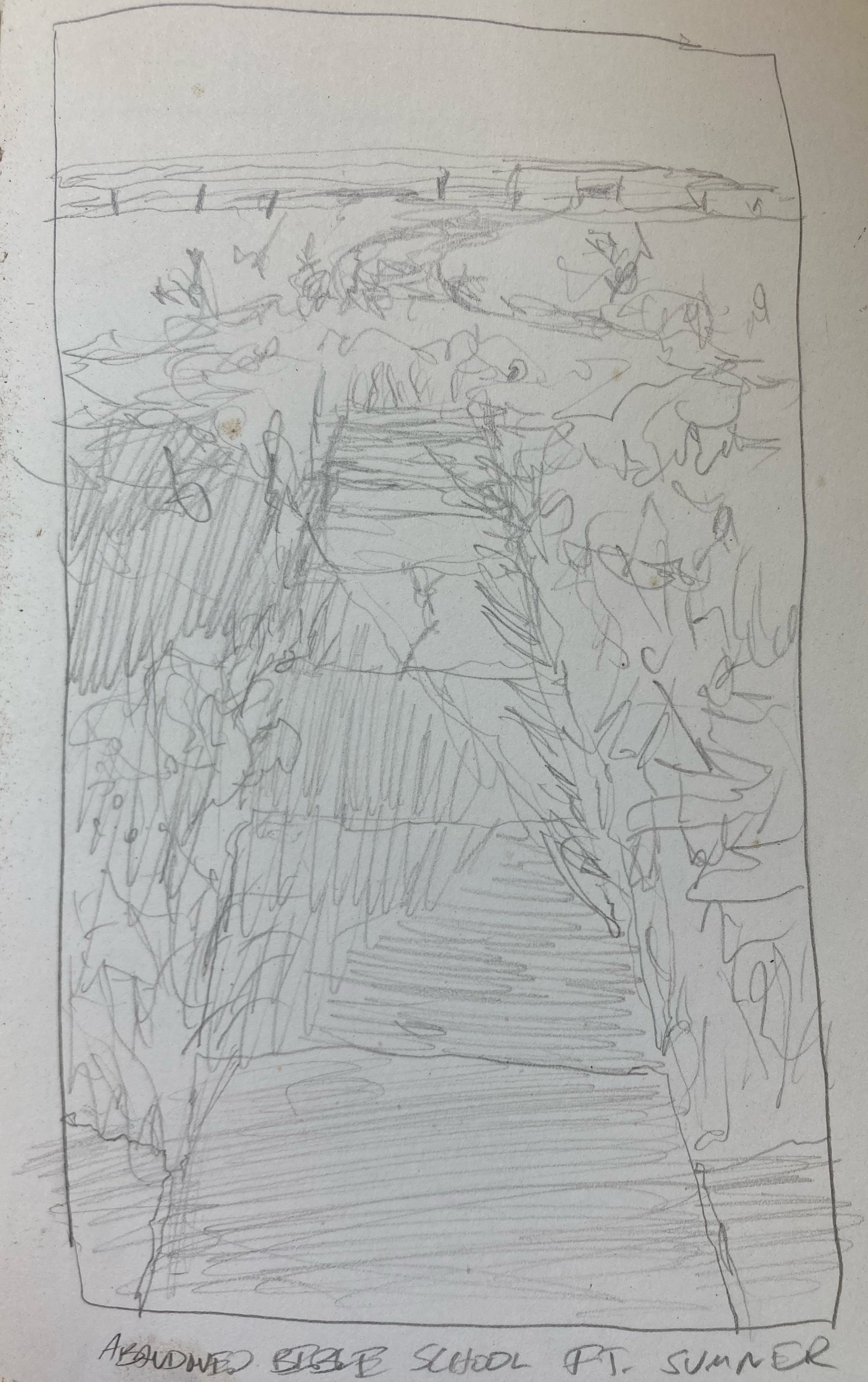

The installation of work at the abandoned bible school near Fort Sumner, New Mexico is the first in which supports for paintings were built to specific sizes. This is most apparent with the painting “Archaic Brother,” which was made to fit the exterior alcove on the school’s façade. One would think it might once have been a window, but I could find no evidence. I found, instead, four holes in the wall precisely where one would expect bolts to have once fastened a cross to it. The painting itself was made for the alcove, responding both to the wall it rests on and to the vast flat landscape in view across from it.

Archaic Brother | Installed in Abandoned Bible School at Fort Sumner, New Mexico

On earlier visits to the school, I sat for meditation on the front steps and made drawings afterward. There I noticed a strange and suspicious thing.

Always there are crows on the distant fence and in the nearby cottonwoods. Relaxing my eyes on the field in front of me, I noticed the desert grass is shaped differently in the areas around the entrance walkway than in the areas farther from it. The overall shape the different grasses made seemed to be that of an enormous crow with its wings outspread. One wonders whether anyone else would have seen the shape in the same way I did, and, if not, to what degree my peripheral awareness of the actual crows informed the way I understood the physical reality of the grass in front of me. This is the sort of question that comes up for me time and again. Often I wonder what constitutes objective reality and to what degree my visual interpretation is to do with it. I continue to wonder about what it means to respond only to what one sees as opposed to what one imagines. One might think of Van Gogh while reflecting on such a question or think of the Zen idea that the world is, in a sense, a portrait of our own minds--in short, a projection.

Perhaps one of the most important things I’ve learned from painting over so many years is how both to value my own sight and intuition while, at the time, seeking to understand its deep unavoidable bias.

Over the past couple of years, though, I’ve noticed a shift in how I see, which seems to correlate with meditation practice. As I live on one of the branches of the Nihil route overlayed on the New Mexico map, I will frequently make drawings in the places I sit for meditation, from the BLM land near my house, to the land in Cibola National Park and the Sandia Wilderness, also nearby. I’ve recently taken greater notice of negative space between landscape features such as boulders, junipers, cactuses, and so on. These seem to provide a useful focal point for controlling the breath. As I always sit outdoors, and never in the same place twice, no two experiences are identical.

Archaic Brother (Detail)

Archaic Brother (Sketches)

One occasion recently was unusually powerful because the shape found in the negative space seemed to me conscious, as if I were confronted by another. I don’t profess any belief about what this means, but somehow, when it happens, I will sometimes connect this perceived consciousness to that of my deceased brother. I have no conviction that it has anything to do with him or something like his ghost, but I trust the value of the encounter and the reality of my own idiosyncratic dynamic with it.

Archaic Brother | Mixed Media on Canvas, Linen, and Burlap | 2022

On this day, the drawings I made of the area of negative space were roughly diamond shaped. As with the layers of “Archaic Brother” which included references to the crow-shaped grass in front of the school, there are also layers in the painting, which included references to the diamond-shaped space between junipers. Both, incidentally, took on similar proportions on the canvas, and that ratio fit well with the distances between holes in the exterior alcove of the school.

In the course of making the painting, I only looked at my own rough sketches of the landscapes where I sat during meditation. I never looked at any figurative drawings. When, in the late stages of the process, a figure began to suggest itself, it came as a great and welcome surprise. It constituted a figure-ground reversal in which all that had been negative space in the painting came forward in the figure itself. Though I’ve made many paintings which began with the figure only to end up as abstracts or landscapes, “Archaic Brother” is the only painting I’ve made which began as an abstract/landscape and ended up a figure.

Of course, I can’t escape the obvious similarity to the crucifixion. It’s not totally coincidental that it should appear so, given that the overall proportions somehow conform to the cross. I welcomed the synchronicity of the outcome in relation to the wall on which I hung the piece. Yet, emphatically, I insist it was never a part of my plan. What meaning, after all, could I want from a crucifixion painting, especially for a project called Nihil, in which I am not seeking to make meaning? I would have thought it too stupid to deal with the crucifixion for the purpose of displaying it once on an abandoned bible school. If I had premeditated the meaning of doing so, it would have been meaningless. Having arrived at the image by accident, it now seems meaningful. But why?

If I place myself again at the scene of the original encounter, gazing onto the negative space between junipers, I suspect my attribution of this sensation to my deceased brother arose out of need. I will sometimes experience confusion between what I attribute to him, the once-living boy, and what I attribute to his absence, or trace. It’s important for me to remember that he was a baby when he died and that my memories are vague and few. The “Archaic Brother,” it should be mentioned, has become a part of the lexicon of Nihil, one of its central tenets even, an abstraction meant to speak of, let’s say, an archetype of absence, in which memory is implicit.

Archaic Brother (Detail)

In my own life, the experience of my brother vanishing suddenly continues to ripple outward and leave its traces. I believe this is specifically to do with the lack of closure around the traumatic and unjust circumstances that caused his death. From that day until now, no one who knew him has ever put those words around it, out of shame perhaps, and for fear of what it could mean for those involved. The shape that all our lives has taken and continues to take in the aftermath of this singular event does so in silence. It has never been spoken of with the care and dignity necessary to pass from its haunted silence into catharsis and healing. It’s as if we feel we don’t deserve to speak of it. I myself have long feared doing so; even now I cannot write the whole story.

Archaic Brother | Installed in Abandoned Bible School at Fort Sumner, New Mexico

It is the unwritten story, I believe, that lives in my body, just as it does in the bodies of my family members. But although it lives in all of us, it manifests differently from one to another, and it’s in my midlife, in the desert I inhabit, that the story pushes its way to the surface, until my own consciousness is externalized as other. This other brings friendly insight; it clears inner pathways, leaking out and hovering in the midground between myself and the external world. It gives permission to know deeply and confidently what I didn’t know I knew, beyond the limits of rationality. I experience a deeper sense of trust and sharper attention, though toward what I don’t know. The experience is meaningful though I don’t know what it means. I experience the Archaic Brother as both a confidant and affirmation of the value of my own heart and the work that comes from it. It is somehow in this absence, this Archaic Brother, that I feel spoken to and recognized more profoundly than anything I find in the social reality of my own time.

Feeling presence in absence, I am not unique. What is the Christ figure to those who believe if not what I have described in my own experiences? It seems, again, non-coincidental to me that the figure ought to arise in the painting; I’ve come out of a Christian tradition. I might not have a literal belief in the claims about resurrection and so on, but I find death and resurrection in my own life, again and again. I do not think this particular god image could hold such mythic power if it didn’t reach into the most profound feelings of loss and brokenness we all must experience at some point in our lives. Public language puts severe limitations on our ability to address this subject meaningfully, but we are not so limited in private language. I am thinking here of Jewish philosopher Martin Buber’s book I and Thou, which is among the canon of philosophical works that has most affected my understanding of how to comport my life and work.

The You encounters me by grace—it cannot be found by seeking. But that I speak the basic word to it is a deed of my whole being, it is my essential deed.

The You encounters me. But I enter into a direct relationship to it. Thus the relationship is election and electing, passive and active at once: An action of the whole must approach passivity, for it does away with all partial actions and thus with any sense of action, which always depends on limited exertions.

The basic word I-You can be spoken only with one’s whole being. The concentration and fusion into a whole being can never be accomplished by me, can never be accomplished without me. I require a You to become; becoming I, I say You.

All actual life is encounter.

And later:

…as he beholds what confronts him, the form discloses itself to the artist. He conjures it into an image. The image does not stand in a world of gods…of course, it is “there” even when no human eye afflicts it; but it sleeps…

Archaic Brother | Installed in Abandoned Bible School at Fort Sumner, New Mexico